Posted March 20, 2025

The Interview – Nick Green

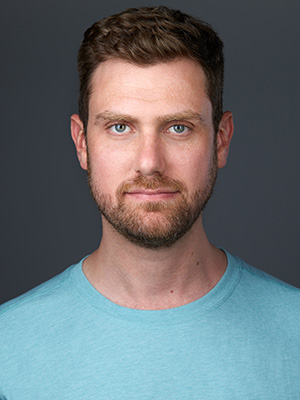

Nick Green

Nick Green is a Dora Mavor Moore Award-winning playwright who is originally from Vancouver, currently based in Toronto. Favourite writing credits include Dr. Silver (book, South Coast Reperatory Theatre, Pacific Playwrights Festival); Happy Birthday Baby J (Shadow Theatre); In Real Life (book, Musical Stage Company/Canadian Music Theatre Projects); Every Day She Rose (co-written with Andrea Scott; Nightwood Theatre); Dinner with the Duchess (Next Stage); and Body Politic (lemonTree/Buddies in Bad Times; Dora Award, Outstanding New Play-General Theatre). Nick is a graduate of the University of Alberta BFA Acting Program.

Nick, your powerful play Casey and Diana has earned rave reviews from critics and audiences alike, and it’s getting productions across the country. Tell us about the play.

Working on Casey and Diana has been one of the most special experiences of my life. The idea sparked when I was doing research for Body Politic at the Toronto Reference Library and saw an article while scrolling through microfiche. I sort of filed it away for later. Fast forward a couple of years when I had a meeting with Bob White at the Stratford Festival, and he invited me to pitch some ideas. I threw this one out there and he leapt at it. Bob was an incredible champion for the project all throughout its development. Right away I reached out to Casey House, and they were open to meeting and kind of just welcomed me in with open arms.

I won’t lie, it was a tough play to write. I remember going on a little mini-retreat to a friend’s cottage in the middle of winter and the enormity of the entire thing kind of landed on me like an avalanche. There I was setting out to write about a beloved figure and a hugely significant Canadian institution WHO DO I THINK I AM?! There were a lot of long walks, a lot of long baths, and a lot of days spent watching Drag Race when I should have been writing.

Eventually I forced myself to start writing. I always start with writing a monologue that is a character trying to get something they want by telling someone else a story. Sometimes it makes it into the play, sometimes it doesn’t. In this case, I had an idea of who I wanted Thomas to be, so I sat him up in bed and got him to tell Princess Diana about the morning he watched her wedding. It unlocked so much for me about how he speaks, how he tries to relate to others, and what he ultimately wants from Diana, from life, from others. At the end of the exercise I found myself writing “When I go, I want my ghost to have a train. Is that too much to ask?” That became such an important statement for me. A train means grandeur and opulence and fantasy, yes. But a train is also something that follows behind, that lingers when you’ve passed someone. It is something of you that can be touched and held. Thomas wants to go out in a way that feels special, but also wants to leave something behind and be remembered. Writing that was a really exciting moment for me, which isn’t to say I didn’t go on to bang my head against every wall and consider quitting a million times…

The run at Stratford was an absolute dream come true. The director of the original production, as well as several subsequent ones, Andrew Kushnir, is an old and close friend of mine, so it was very special to share this experience with him, and I love his work on the show. From the beginning, the rehearsal room was just brimming with love from everyone who worked on the piece. The cast was remarkable and some of them have become great friends of mine. The Festival truly embraced this play and treated all involved, including those at Casey House, with huge amounts of respect and kindness, from the way they provided the reflection room to the various events they held.

All the same can be said for the Soulpepper production that followed, where the artistic leadership welcomed me and this production with the most incredible enthusiasm and generosity. Soulpepper was this wild ride of “YES!” From the start, I remember Luke Reece sitting me down and saying “We aren’t going to string you along. We want this play, and if you let us, we are doing this play.” Even on the night when I sheepishly asked if I could get comps for a bunch of Toronto playwrights—which is a thing I’ve been trying to get going in the city—and not only did Soulpepper say yes, Weyni hosted a party for us all at her house afterwards!

The play has many upcoming productions, which of course is such a dream for a playwright. It just finished it’s run at Theatre Aquarius, and that production will be opening in a few weeks at the Royal Manitoba Theatre Centre. In April, the play opens at Neptune Theatre in Halifax, then a week later a different production opens at the Arts Club in Vancouver (just two days before Every Day She Rose opens in Vancouver at the Cultch!) In the fall the play opens at Yes Theatre in Sudbury, and then in early 2026, there is a co-production with runs at both the Citadel in Edmonton and Alberta Theatre Projects in Calgary. Beyond that there are four more productions—two in the US, two in Canada—that will be announced down the road.

I really, genuinely pinch myself every day. It’s bucket list stuff.

Several of your other plays—such as The Body Politic, Every Day She Rose (which you co-wrote with Andrea Scott), and Happy Birthday, Baby J.—could be considered “political,” in the best sense of the word. Do you consider yourself a political writer? Do you make a conscious effort to explore LGBTQ+ or gender issues, or do your characters lead you there?

I think I would consider myself a political writer in that I certainly don’t shy away from topics that are very politicized, and I tend to have a perspective that I am offering. These are very often related to queer stories because I love being queer and I love queer people and queer history. Plus there’s still so much ignorance and intolerance to be battled, especially in these terrifying times! That said, I’m allergic to one-sided stories. I really do aim to present different perspectives, and I try to write characters who have perspectives that one could understand, as well as a humanity that makes them hard to dismiss.

Dinner with the Duchess, your drama about an artist at a critical moment in her life,premiered last summer at Here and Now Theatre in Stratford, and the production just had a successful run at Toronto Crow’s Theatre. Why did you want to tell this story?

You asked before about whether characters lead me in my writing, and I would say that this is definitely the case with Duchess. I sat down to write that during a crossroads in my life. I hated theatre. My entire life has been devoted to theatre. I mean since I was like eight, I have been eating and breathing this art form. And yet in my early thirties, after putting in almost a decade of trying to do it professionally, it all just felt so toxic. It was practically all that I was, and I resented it so much. So I set out on this play wanting to write about how a life devoted to your passion has the potential to destroy your love of it.

As I mentioned before, I started writing a monologue in which the central character Margaret was telling the story of Wilma Norman Neruda being humiliated at a concert, and by the end of that monologue I had met a character who was clearly going to tell me exactly what needed to be said in this play. From there, the play became about much more than the experience of working in the arts. It became about legacy and gender and transgression and forgiveness. The first incarnation of it during the developmental run at Next Stage didn’t quite land the plane, but I’m really proud of where it got to, and all my thanks go to my dramaturg Marjorie Chan for helping me get there.

Nick, I’d like to ask you about your life outside the theatre. You’re a social worker, is that right? How does your work with youth feed your art—or vice versa?

That is correct! After working full-time as an actor and a writer for many years, I came to the realization that it was not the life for me. I remember sitting in the dressing room of an A House theatre before a show I was acting in, thinking, “I wish I was home right now,” and then thinking “Ummm doing this play in this theatre is, like, an example of this career going well, and you’re wishing you were watching Real Housewives?” No no no, a full time artist career is WAY too hard. So that experience, paired with coming very close to a career-defining role but losing it due to my height, led to me going back to school in my late twenties.

After a year in Open Studies at University of Toronto—which I always recommend to anyone thinking they might want to try something else—I landed on social work as the path I was most interested in. I’ve always done a lot of volunteer work with the queer community and had just finished an incredible volunteer position in the palliative care unit at St. Joseph’s, where I learned from the most amazing social worker. So I applied for a program at York and absolutely loved the training.

Social work is such a broad field. There’s clinical work, community engagement, medical fields, family fields, school settings, grassroots organizing, radical resistance efforts, and so much more. Ultimately the study of social work is about opening your mind up to the ways that the structures of society advantage some and disadvantage many. In order to be someone who can provide supports to others, you need to learn to think critically about how society is built through language and power and history and violence, and really understand the ways that systemic/structural/institutional oppression have incredibly dire impacts on so many people’s lives. Most of my work has been with children and families, as well as working with male perpetrators of domestic violence.

It’s a tough, tough field, and some days there is NO WAY I can do any writing, much less work on something heavy. But most of the time it’s a great escape for me, a place for me to put thoughts and feelings. Both jobs require such interest and observation in/of the human experience, so they definitely feed one another. That said, I have some firm boundaries around overlapping these aspects of my life. I’ve never brought any kind of experience from my social work life into my writing, and I pretty purposefully stay away from issues and topics I directly grapple with at work. I don’t think it’d be healthy for me to take on some of these issues in both of my work days.

What are you working on now? Could you give us a sneak preview?

I can be more specific with some projects than others. I was fortunate to get a commission from Soulpepper this year and am working on a very intimidating adaptation of The Divine Comedy. I’ve been working with Anika and Britta Johnson on a new version of their cult musical Dr. Silver, which has been developed with South Coast Repertory Theatre in California over the last few years. I’m also working on a slightly secret musical that has some very exciting potential that hopefully I’ll be able to talk about in the near future.

I have three new ideas that I am excited about too, but I’m waiting to find a theatre company that might be interested in developing them before I put pen to page.

And finally—do you have any advice for aspiring playwrights?

Yes! I always jump at this opportunity—not because I think I’m the expert but because I know how much I gobbled up advice when I was getting started. Here are 10 tips because I love a list:

- Your first draft is not going to be good. As Stephen King says, the first draft is for you to tell yourself the story. Don’t get stuck on making it great. Tell yourself the story, then rewrite and rewrite and rewrite.

- Get your work out there. Don’t wait for your dance card to be… stamped? (I don’t know what people did with dance cards). I remember Nina Lee Aquino giving me that exact advice after Body Politic, and I wrote Dinner with the Duchess like two weeks later. Do the Fringe, enter short pieces to festivals, get your friends to read your plays in your living room and invite two people to come and listen. Just get it out there.

- Read a million plays. I read at least one per month. Toronto Public Library has a big catalogue of digital plays that you can download for two weeks. Read Canadian plays for sure—the classics and the work being done today. I have many playwriting heroes, but the people who inspire me the most to actually write are Kanika Ambrose, David Yee, Hannah Moscovich, Mark Crawford, Erin Shields, and so, so many other Canadian playwrights who are pushing the art form forward.

- Canadian playwrights are the absolute best and, in my experience, they are so willing to welcome in new playwrights, mentor them, and send them pdfs of their unpublished work. They PROBABLY can’t read your play and give you feedback for free, but don’t be shy about reaching out to say hi, ask questions, and generally just try to connect.

- Make it a mission to better understand what conflict is. It’s not a simple concept. Conflict is deeply complicated. It’s everywhere, and it’s integral for a good play.

- Do not DARE waste a workshop. This is a bit of a pet peeve of mine. If you have the opportunity to workshop a play for more than one day, for the love of all that’s holy, do some REWRITES. Of course, you’ll want to hear it read a few times, and it’s always nice to get people’s responses—especially if it’s flattering. But it is a missed opportunity if you aren’t taking time to try some things. Think that it’s structurally perfect? Write a new monologue for a character with some backstory. Still think it’s perfect? Try rewriting a scene just for the hell of it. There is literally nothing to lose. Those in workshops of my plays will tell you that they return to the room with entire acts re-written. Casey and Diana was a one-act for the first two days of one workshop period, and then a two-act for the last two days.

- Write the play that scares you. I’m not talking about putting unresolved trauma out there. I’m talking about the one that asks you to push the way you think.

- Watching reality TV helps with writing dialogue. There, I just justified writing off my Hayu subscription on my taxes.

- Go see theatre as much as possible. Arts worker tickets are your friend. Not only is it important to feed your craft and grow your sensibilities around what works and what doesn’t, it’s also so important to connect with the theatre community. Understand what’s being programmed these days. Figure out which local actors inspire you (I have dibs on Laura Condlln, so don’t even try). And above all, show support and love to your colleagues. This job is LONELY and everyone in theatre gets to work with playwrights except other playwrights. Go see that new play by a local playwright. Sit down prepared to love what they’re doing. Remember that other playwrights are co-workers, not competition. And when you’re done, reach out to that playwright to give support. Trust me, we ALL need to hear nice things when our work is out there.

- Seek to love the art in yourself, not yourself in the art.

-

Casey and Diana

$9.99 – $17.95