Posted March 15, 2024

The Interview – Kelley Jo Burke

Kelley Jo Burke

Kelley Jo Burke is an award-winning Regina playwright, creative nonfiction writer and documentarian, and was for many years host of CBC Radio’s SoundXchange. In 2017, she and composer Jeffery Straker won the Playwrights Guild of Canada’s national Best New Musical Award for Us, which premiered at the Globe Theatre 2018. Kelley Jo’s other plays include The Lucky Ones, Somewhere, Sask., Ducks on the Moon, The Selkie Wife, Jane’s Thumb, Charming and Rose: True Love, The Curst, and the upcoming Greensleep. She’s also written three books, and eight creative nonfiction documentaries for CBC Radio’s IDEAS. Kelley Jo was the 2009 winner of the Sask. Lieutenant-Governor’s Award for Leadership in the Arts, the 2008 Saskatoon and Area Theatre Award for Playwriting, and has received the City of Regina Writing Award four times.

Kelley Jo, you’ve worked as a playwright, director, memoirist, performer, professor, dramaturge, editor, documentarian, broadcaster, and more. Why do you think you like to wear so many hats?

First of all, I don’t think it’s different hats. I think it’s all one hat. I think I work talk. And I think it’s a physiological issue as much as anything because I only just recently learned that not everybody thinks in speech. Some people think in pictures and some people think in concepts, which I find eerie. I think they’re all aliens. But I think in conversation; I think in spoken English—or spoken French, if you give me enough time. All of the work I do is about processing ideas through the generation of speech. I’m an extroverted thinker. I don’t know what I think until I say it. I am often as surprised as anyone else as I see something go by and I go, “Oh, that’s what I think!”

And so I have worked in speech my entire life. I started as an actor, in the young company in the Manitoba Theatre Workshop, (which is now Prairie Theatre Exchange,) and they figured out somehow that not only could I talk in iambic pentameter, I could write iambic pentameter. And so I became my company’s playwright as well as an actor. That made me a writer. My theatre company made me a writer because I was writing speech. If I had gone the traditional route of a lot of young writers, which is to move directly into prose, I don’t think I would have become a writer as quickly.

And then I was a journalist—journalist is in the list, too—but I was primarily an essayist and editorialist. Again, because it’s speech. So moving into CBC came naturally from that. Then I was a broadcaster, and then I was a radio playwright and I was doing stage plays at the same time. So I think it’s all the same job. I think it is creating. Generating ideas and putting them into conversations. I think I’m having an ongoing conversation with the world, and I’m doing it through a number of venues.

So, all one job. But playwriting is so hard. I teach playwriting, and the first thing I tell my students is: Find another form. If there’s any possibility for writing in another form, please, God, do it. Even film scripting is full of heartbreak, but if you actually get a gig, the money is so much better. Playwriting is such a challenging form because you really only have what people say and what people do to tell the story. That’s it. The first thing I teach my students is: If you do any cheesy exposition, you fail my course. So don’t do it. “What is the knife that’s in your hand that Jerry gave you when you were wearing a green dress?” We never do that. It’s a very, very challenging form and it’s collaborative…and I hate people! (Laughs.) So it’s a really hard form, but it is the only form that I work in where you get to be magic. You get to make a thing happen in real time, in a real room with people for a moment. All the “I’m wearing clothes from Value Village and the set’s cardboard” and all that stuff—all that stuff goes away. And for a moment a real thing happens. Something only existed in your imagination, and it happens right there in front of people, and people react to it like it’s happening. And that’s just addictive. So even though it’s the hardest form that I work in, it’s also the one that’s hardest to walk away from.

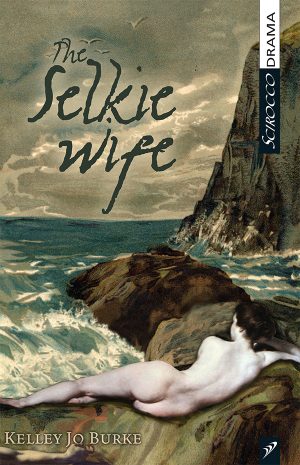

Your recent play, Rigby, won the 2023 City of Regina Writing Award, an award you’ve won an incredible four times! Rigby features banshee characters who are living on the border between life and death. The Selkie Wife, published by Scirocco Drama a few years back, is a modern riff on the old Scottish legend of the seal who turns human on land. Your upcoming play, Greensleep, which focuses on the climate crisis, is subtitled “A Fairy Tale for the End of the World.” Tell us a bit about the use of folktales and fairy tales in your work.

I discovered the 398.2 section of the library when I was four, which is the fairy tales and folklore section. I stole a copy of D’aulaires Book of Greek Myths from my Grade Three class, and I have it to this day. (I think I have guilt, but it’s still my book). I became deeply enamored of the kind of story that passes hands. You know, it becomes this thing made out of bone where the bits and pieces are all gone, but it just passes hands and it gets smoother, and everyone that holds it changes it a little bit more. I think that sort of meshed up with the part where I deeply, deeply wanted to be Mary Poppins when I was a kid, and I wanted to be able to do magic. And so I saw the fairy tales and myth books as basically on-the-job training, and I read them so that I could learn how to do magic, too. It became a deep part of my life.

And as I got older and I began to investigate those stories with my understanding of the adult world, I began to see how those stories were baked into how we understand the life’s journey. Like, really, those stories are what we pass from hand to hand, generation to generation, to tell the next generation what to expect and how to get through it. So I began to feel like I could have a small part in that. I could take those stories and put them through my hands and see what I had to share with that structure.

On a more prosaic note, I hate plot. I just hate plot. I hated plot when I was 25. At 62, I am over plot. I have read thousands and thousands of books. I’ve seen thousands and thousands of movies. I have heard story over and over and over again, and it comes down to about seven plots and I’m tired of it. I’m so interested in anything that I can watch or read where I don’t know what’s going to happen next. And so I love to build with stories that people think they know, and then say, “Yeah, no, but let’s talk about it this way.” I think that’s how I started to mess with fairy tales. My very first play was rooted in mythology. The next one was about images of women. The next one was about a very specific fairy tale. And I come back to myth and fairy tales again and again. Because they’re my Bible, you know?

You’re not afraid to use your own life as material for your work, either. Ducks on the Moon was based on your experiences as the mom of a child with autism, and your splendid 2021 memoir, Wreck, is a brave and vastly entertaining account of your struggle to understand yourself and to come to terms with your family’s history. Is it difficult to share your own personal stories with an audience?

Simple answer: No, it’s not difficult. It probably should be. But, you know, I belong to a support group for over-sharers! The first book where I started working with memoir was Ducks on the Moon, which was a play first. That came out of the first five years with my youngest kid who was diagnosed with being on the autistic autism spectrum. They were the five hardest years in our family’s life to date. I just had been handling what was going on in my life by coming up with funny stories. To talk to people about why I hadn’t slept in five days. Why I don’t remember 2003, in its entirety. I had all these stories because that’s what we do. That’s where the fairy stories come from. That’s where the folk songs about mortality come from. We take the stuff that’s too heavy to bear, and we put it into a basket of story and song and language. We put a catchy melody or a funny punchline on the end of it so that it’s bearable, and that’s how we hand it to other people, so that they can learn from our experience, and so that we can feel supported in what’s happening to us. And so telling those stories was part of how I survived. Taking them and putting them into a one-person show was literally just because I wanted to be able to talk to other parents who were going through that stuff. But then it turned out that people who did not have children on the autism spectrum but were simply carrying something heavy, too, really enjoyed the show and really wanted to talk to me about it. And then it became a documentary, and a book, but the talking part of it…like I said, it’s just part of my job to talk things through. And so talking through what happened with our son and turning that into something that I shared with other people was incredibly natural and simple.

And then the second memoir, which is about anxiety, but it’s also about how my grandpa kind of killed my grandmother. Again, it was complicated and needed to be worked through. And I had these stories that I told because how do you talk about something? I got scolded by a journalist who I was interviewed by for the book because he just went, “You can’t write about stuff like that and call it a comedy!” And I’m going, “What else do you do? How do you get through this life? What am I supposed to do?” And I was just stunned. There are some things where you have to be pretty careful where you make jokes, and you have to be very, very aware of who the joke is on, but I’m almost always writing about the joke being on me, so I feel pretty safe about that stuff. I find the human condition fairly lonely. The space between the ears is a pretty lonely space, and our capacity to get any part of it out and share it with another human being is pretty limited. You try, and then you look up and you’ve been married for 40 years and your partner goes, “I never knew that.” So the part where you can take something from your life, turn it into story and share it with other people, have that moment of communion with other people—it’s the least lonely moment I ever have.

I toured Ducks for several years, and there would be this moment where I would be talking about the five hardest years of my life, and I would look up and there would be someone sitting in the front row. I had been talking for maybe four minutes, and the tears were already pouring down their face while they were laughing. And I would sort of look out at that face and I’d go, “I got you. I got you. We’re going to get through this one together.”

What a privilege. You stand up on a table with a light on your face, and you get to talk to people, and they’ll sit and listen to you, and you get to have that moment. The first time I did that show, I thought people would chase me out of the theater. I thought they’d come seize my kid. Like, I thought they would send social services to my house and take my kid away. And instead people would come up to me and go,” I’d like to hug you. Would that be okay? Can I hug you, please? I don’t know you very well, but I think you really need this.” Okay. Okay.

It was such an honor and it felt so beautiful. Again, addictive. So, I know if I can do a good job of it, if I can have integrity, if I can work within some pretty strict ethical bounds I have around memoir—then I don’t have any trouble and my family doesn’t. I check with my family about everything.

Kelley Jo, you’ve also written musicals: your recent “alt-pop musical fantasia” The Curst, featured the music of the band Library Voices, and Us, a musical written with composer Jeffery Straker was inspired by the fyreFly leadership camp for LGBTQ+ teens. What can you tell us about your experiences with musicals?

I did Somewhere, SK with [singer-songwriter]Carrie Catherine. I did Us with Jeff Straker. I just finished last spring The Curst with Library Voices and…Okay. So that’s just indulgence on one level. I was blessed. When I was at CBC, I was an arts and literature producer for CBC, and one of my jobs was to produce readings. I discovered very early on that it was a great joy to me to find the right music to go with the words. And I developed this tremendous love of word and music production. I’m a storyteller as well, and I started working with musicians when I tell stories. And that was just magic. Oh my! I worked with a saxophone player once when I was telling stories, and it was like, “I could do this for the rest of my life!” So I love words and music. And then there are some astonishing musicians, really amazing musicians in Saskatchewan, and I could hear the stories in their songs. So Carrie [Catherine] came to me and said, “I want to maybe have a song and story performance piece that I can tour.” And I wrote Somewhere, SK for her. Jeff [Straker] and I had both been embedded artists at Camp fyreFly, which is a camp for queer kids, and said, I think there’s a show there. And that was…I mean, Jeffery has insane musicality, and I just I knew that he would be very, very good at that. And he was. And then with The Curst, Library Voices is my favorite band, probably my favorite band in Canada. They were very active when I was at CBC, and I thought they were incredibly gifted; I thought they were going to break big. And then something else happened. I came to them after they had all moved into other phases of life and said, “I can hear that story in your songs. And I think I can make a musical out of it.” And I talked for 45 minutes and I was super nervous. And then at the end of it, they went, “Oh, okay.” And so we worked together and we built The Curst. And it was beautiful. It was. But so self-indulgent. Like, I just I’m going to get a bunch of actors together who also are stunning musicians, and I’m going to get them to play my favorite music for two hours on a stage!

Your plays have been produced by many theatre companies in various cities, but you have a special relationship with Meacham’s Dancing Sky Theatre. For people who have never been there, can you describe what makes Dancing Sky special?

A couple of years ago, we did this big celebration for Dancing Sky because they were having their 25th anniversary. Me and a number of other playwrights who’ve been supported, including James O’Shea. There was a big “do” at the theatre (before the pandemic) and we talked about the unicorn that is Dancing Sky because it shouldn’t exist. If it existed, it should have been one of those things where people went, “Yeah, we’re going to do this thing,” and then it would have just absolutely petered out and gone bankrupt after about 18 months. But it’s going 30 years plus now and it’s magic. It is the only theatre in Saskatchewan that produces only new Saskatchewan work. They use entirely Saskatchewan casts. They use a Saskatchewan musician for every show; there’s live music in every show. It is in this beautiful little community hall in Meacham, Saskatchewan, which is about 30 minutes outside of Saskatoon. Angus and Louisa Ferguson, the artistic director and his partner, their sweat is in every piece of wood and every piece of equipment in that theatre. It is! It’s got blue sky on the roof and twinkle lights that run off the solar system that they built themselves. It can seat 130 in a pinch. I had a friend fly in from Penticton for the last show, and she said, “When you told me there was going to be an entire rock band, I thought it would be a bigger stage. And then when I walked in and saw what the stage was, I went, ‘Oh, this is going to be awful.’ And then they got up and it was fantastic.” They use this beautiful hall…Angus has been working with that space for most of his adult life, and he’s a genius for making things live in the space. There’s also a lovely kitchen on the side so that if you come out to Meacham, you can have dinner or brunch before the show with a professional chef making the meals. It’s magic. It’s a magic place. And Angus is, you know, he’s the bumblebee who flies. He just keeps going, and…you know how it happens in arts organizations when somebody is just keeping something going with the sweat of their brow for decades? They get mad. They get burnt out. Angus doesn’t. He has come up with a way of managing the shows that allows him to continue to work in balance with the rest of his life. He continues not only to build the sets, direct the shows, help with the promotion, but also to run the bar during the run! He also brings tremendous artistry and compassion and empathy. And he’s the best dramaturge I’ve ever worked with, and he’s been my dramaturge on a number of shows. He’s a gift to the playwrights here in the province, and I can’t believe my luck that I get to work with him regularly.

His partner, Louisa, who’s the artist, who also can build anything, give anything…Lou has gone off and become an important visual artist. But for decades, she was the reason why everything happened, because she ran the box office and she did all she did all the money stuff. The two of them were and are the hardest-working people I’ve ever seen.

Could you tell us a little more about your two newest projects, Rigby and Greensleep?

Yes, because these two projects are both incredibly dear to my heart. Greensleep is a commission, and I don’t usually take commissions because I’m not enough of a business person to be good at that. But, during the run of The Curst, while I was sitting in the dining room at Dancing Sky having my dinner, Angus kind of crept over and went, “Kelley Jo, how would you feel about a commission?” And I went, “Great.” And he said, “We have some ideas that we would like to explore in the theatre, and we think that you would be great to write it.” And I went, “Okay.” And he said, “And we’d like to do it next May.” And I said, “Angus, it’s May now. My show isn’t down yet. You can’t put me up two Mays in a row!” And he went, “Oh, I think we can.” So they sent me this book, which is called The Flowering Wand: Rewilding the Masculine by Sophie Strand. Sophie is a poet-environmentalist, and she has taken some major myths and fairy tales from Western culture and taken them back to their origins, which are pre-Christianity, because most of those stories come out of nature-based pantheons, and they got shoved into Christianity and lost some aspects along the way. The book is a series of essays where she investigates different stories, and there was one that Angus particularly loved, which was the sort of proto-Sleeping Beauty. And he went, “This feels like your wheelhouse.” And I read it, and I came back to him and I said, “I love this book, Angus, but I don’t do earnest. I can write a play, but this is very earnest, and I don’t do earnest.” And he went, “I know, but you do do ‘once upon a time.’” And I said, “Yes, I do.” And he said, “Okay, you don’t have to be earnest, but let’s see what you got.” And I came up with Greensleep, which I don’t know where it came from. It’s bonkers! I certainly referenced the book that they sent me as the prompt, and then I spent months before I started writing anything. When I got home in May, I started looking at end-of-the-world scenarios. That was all I read for eight weeks: the world after humanity, looking at how long it takes after people are gone for the Earth to heal itself, different projections for how we pull it off in terms of actually wiping ourselves out. So it was a fun eight weeks. (And you have to put in parentheses: “Kelley is clearly being sarcastic at this point.”) But I began to hear in the fairy tale that Sleeping Beauty is really about nature. Go back to the myth of Persephone, and it’s about nature going underground during the winter and coming back up again. And I began thinking about writing a post-apocalyptic story about the world. Closing down and coming back up again. And how that could happen in a way that we haven’t seen before. And then my other prompt that I got from Angus was, “How would you write a play where the natural world was a character, not part of the setting?” And I went, “Music. Everything sings. All of nature sings. We all sing. It’s perfect. I can make the natural world be a character on stage through music. And that would be absolutely how you would do it.” And then we started talking about puppetry and music and how all that would come together.

So I have written a play where the natural world is an active character throughout the play, and I never would have done that if Angus hadn’t asked me. I’m far too human-centric to think of that. But that’s why collaboration is so amazing, because you go places that you wouldn’t go by yourself. We have an amazing musician named Edith Rattray, who’s an environmental musician, who’s going to be creating the music of the natural world during the play. And that’s how we’re having a play that is post-apocalyptic and that I insist is a comedy, because I don’t do earnest. And so we will see how it goes. At this point in my career and at my age, doing something that scares me is really good for me.

And then Rigby, which I wrote coming out of the pandemic. It was awarded the City of Regina Writing Award, which I’m so grateful for. Covid and the pandemic and a few other things took what had been sort of a simmering disability to the next level, and I’m in a chair now. Not a wheelchair—I’m on a walker. My feet have been gone for ten years, and my hands went, and I suddenly looked up and went, “Oh, I’m a disabled artist.” And I had been for a while, but it was something that was not particularly visible, and so I chose not to identify that way. But now it’s absolutely, unavoidably visible. And I was processing that. And one day we were driving along, and I saw a woman in a heavy coat with a toque sitting in a walker chair like mine, waiting for the bus with her arms wrapped around her, and her face looking like she would make the Easter Island statues look like they were wacka-wacka funny dudes. Because this was a very grim person. And I looked at this person, and for the first time, because I’m kind of dumb that way, I’m going, “There’s me.” I could have been looking at that person any time in my life saying, “That’s me.” We could all look at that person any time in our lives and say, “That’s me.” But I now had a physical reminder of that. And I thought, “Nobody knows what’s inside that person. Everybody thinks they know what they’re saying, and nobody does.” And I thought of them as a cocoon. And that if you could open the cocoon of that hunched figure on the walker chair, you know, rainbows and butterflies and stars and things could burst out of her, because we don’t know what’s inside there. And then I wrote a play about what would burst out of inside of that cocoon. I wrote Rigby.

Because I was dealing with some existential stuff. We all were dealing with existential stuff around death there, in 2020, 2021. Death was very predominant in in our minds to some degree. And I started to think about what would happen if that person in the chair was magic—the person who would come and talk to you before you died. And again, I came back to story and I came up with this idea of these—for the sake of convenience, when I talk about them I call them “banshees,” but not everybody does. It’s not mentioned in the play, but that’s what they are. They’re the beings that come to you in the moments of your death and tell you the story of your life, because people like story, and they like to know that it meant something. And so I said, “Okay, how did she become that? What’s the job like? What happens if various things happen?” Then ultimately I thought, “What happens if one of them falls in love with somebody?” And I ended up with this—again, bonkers—love story. From that single figure sitting by the bus stop. This huge, huge, complex world and fairy tale thing just burst out of her. I just wrote it because I wanted to write it. So it was really delightful when I got the City of Regina Writing Award, because something came out of it. We’re going to be doing a developmental reading of the play this year. And I’m working with and listening to the disability arts company here in town, who have been very supportive.

One of the questions I’d planned to ask you was whether you had any advice for playwrights, but I think you answered that: No cheesy exposition! But would you like to add anything to that?

My other advice for playwrights is: Find your people. Theatre cannot be done in a vacuum. And it’s incredibly frustrating to be generating work and have it sit in your hands while you go, “Now what?” So, you know, when I was a young playwright, I volunteered for everything. I was on the on the Playwrights Centre board, and I was with the Arts Alliance and the Playwrights Union. I’ve been on the Playwrights Guild executive off and on for 30 years—well, only one job, actually. I’m the head of the Women’s Caucus. I was the head of the Women’s Caucus in the 1990s, and now I’m the head of the Women’s Caucus again. So you’ve got to find your people. The happiest person in theatre is the one who has a collaborator who has their back, and you have theirs, because then the magic can start.

-

The Selkie Wife$14.95

The Selkie Wife$14.95